by Daniella Zaidman – Mauer

Amsterdam’s relatively liberal atmosphere helped it to become the European centre of Jewish printing, home to a lively business in Jewish books and the location of the first Yiddish newspaper. Jews and gentiles actively collaborated in the trade of Jewish books. Non-Jewish booksellers auctioned the libraries of rabbis, Christian apprentices worked in the print shops of Sephardic printers, and investors and even Protestant ministers financed the publication of Jewish books.

Amsterdam’s relatively liberal atmosphere helped it to become the European centre of Jewish printing, home to a lively business in Jewish books and the location of the first Yiddish newspaper. Jews and gentiles actively collaborated in the trade of Jewish books. Non-Jewish booksellers auctioned the libraries of rabbis, Christian apprentices worked in the print shops of Sephardic printers, and investors and even Protestant ministers financed the publication of Jewish books.

While publishers and printers usually boasted about their intention of serving the Jewish readers, commercial considerations were a large part of their decision. The publishers realized the international potential of the market for Yiddish books and therefore clung to the use of Western Yiddish, while eliminating local Dutch Yiddish dialects from their texts. An example of this can be found in Yosef Athias’s Yiddish bible (Amsterdam, 1679), where it is stated in the preface that they especially hired a person in order to remove any local Dutch usages of Yiddish from the text.

The biggest export market was in Poland, with its substantial Jewish population. Yiddish books printed in Amsterdam were prominently present at the biannual book fair held during the assembly of the Jewish Council of the Four Lands of Poland. Amsterdam became one of the principal suppliers of Yiddish books intended for the benefit of Ashkenazi Jews.

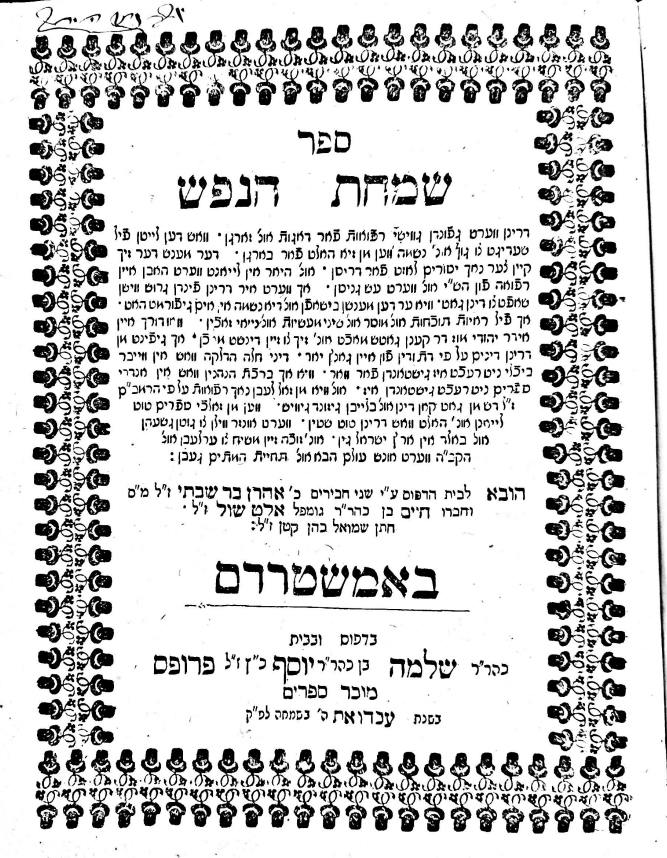

According to Shlomo Berger, circa 320 Yiddish books were printed in the city in the years 1650-1750. The printers of Amsterdam attained an exceptionally high level of typographical excellence, which greatly influenced Jewish printing throughout Europe. Seeking to increase the value and stature of their books, printers printed on cover pages, in small lettering, the location where their books were printed, adding below, in prominent letters ‘באותיות אמשטרדם’ (in Amsterdam letters). Bilingual books in Hebrew with Yiddish translation became common and popular in many Ashkenazi communities in which people often used two or more languages as a ‘linguistic and cultural poly-system’.

Transferring a text from Hebrew to Yiddish ordinarily involved a simplified translation of the original, since the aim was to present the essence of the liturgical texts, its observance and practice of customs in the vernacular. Since Yiddish could not and did not challenge the supremacy of Hebrew, and since there was no movement to have it acknowledged as the canonical language of Judaism, it enjoyed a measure of liberty that the Hebrew did not have. Books from various aspects of Jewish life were published for all ages, from educational materials, prayer books and ethical books to general literature.

Bibliography:

On the Yiddish press see Pach Oosterbroek, “Arranging Reality;” Pettegree and Der Weduwen, The Bookshop of the World; On selling knowledge in 17th century Amsterdam, see Peter Burke, Social History of Knowledge; More on the Yiddish translations of the bible in Amsterdam, see: Marion Aptroot, “Bible Translation as Cultural Reform”; idem., “‘In Galkhes they do not say so, but the Taytsh is as it Stands Here’,” 136-158; Shlomo Berger, Producing Redemption, 19-20; Idem, “An Invitation to Buy and Read,” 31-61.

Biography Daniella Zaidman – Mauer

PhD student at the University of Amsterdam, School of History Research (ASH) Department of Hebrew and Jewish Studies, writing her thesis on Responses to the Plague in Early Modern Ashkenaz: Pandemics and Piety as the Key to Health in Yiddish Remedy Books in the 17-18th Century, under the supervision of Prof. Irene Zwiep and Prof. Bart Wallet; MA Thesis titled Seventeenth-and Eighteenth-Century Yiddish Versions of Pereq Shira (Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 2019), under the supervision of Prof. Claudia Rosenzweig; Publications: see article, Daniella Zaidman-Mauer, “The Power of Song in Amsterdam: Pereq Shira in Yiddish and the Transmission of Piety,” Studia Rosenthaliana, Volume 47, Issue 1, Jan 2021, pp. 48 – 82.